One of the best segments on the old Daily Show was Stephen Colbert’s “This Week in God” – I wanted to have a clip here but WordPress and Comedy Central’s embedding system do not play well together.

A few weeks ago, a Facebook friend of mine asked a question on his feed: Are his religious friends more offended that his atheism means he doesn’t believe in any religion or that it means he doesn’t believe in their religion? I felt I had something to offer to the discussion from a historical perspective. In both pre-modern Christianity and Islam an accusation of atheism was usually considered far worse than an accusation of heresy, false religion, or sometimes even witchcraft, although technically the sin would have been spreading atheism rather than the unbelief in itself. However, instead of just saying that, I decided to be a little cheeky, as one sometimes is on Facebook. I conjured up hyperbolic images of demonic infidels, burnings at the stake, and suffering Presbyterians.

Another friend decided to call me out, calling my comment snarky and unproductive. On reflection, I decided that he was correct. Rather than facilitating the discussion, it put more pious friends, the actual target of the original question, on the defensive, perhaps leading to more guarded answers. I apologized and tried to rephrase my idea in a less dismissive tone. But this raised another question for me: Why did I think that kind of humor could facilitate the discussion in the first place? I actually think it can, but as with any humor, context and timing is everything. We live in an era when much of our substantive social debates, including debates about religion, are conducted by comedians, John Stewart, Stephen Colbert, Sarah Silverman, and Bill Maher. But where I find Colbert hilarious when he talks about religion, I can’t stand Maher, whom I see as a mean-spirited bigot. Why?

Humor is so interconnected with individual taste that you can’t really deduce universal rules. But I think an exploration of examples from across the spectrum might tease out some of the potential relationships between humorist, audience, context, and social effect.

TAKING THE SACRED DOWN A PEG

In the classroom, I’ve deliberately used irreverent humor for a pedagogical purpose. Despite all the disrespectful things said about Islam and other religions in certain corners of American culture, I’ve found that on the whole American students are reluctant to ask critical questions of religions other than their own – perhaps even more than they would with their own religions – although my friends in Biblical Studies may beg to differ. In fact, this is what I see as the central flaw in the way religion is discussed in American public space: People who aren’t seeking understanding speak loudly and disrespectfully while people who are seeking understanding avoid speaking up for fear of causing offense. My own response is to de-sacralize the sacred with humor.

The “Sacred” is an important concept in comparative religious studies, although different thinkers use the term in slightly different ways. While some emphasize the sacred as a person, place, or thing experienced as originating from a numinous realm, others, like Jonathan Z. Smith, suggest the idea of the sacred arises not from some passive experience but rather from the active reverence directed toward a sacred object. This accounts for why one person’s sacred object may seem mundane to another. Furthermore, the nature of this reverence means that the sacred must not be subjected to the types of attention given to everyday people, places, or things. You cannot look at it, touch it, listen to it, walk upon it, enter it, talk to it or about it, depict it, question it, or say its name without either being a special person or making oneself special in some way, such as through initiation, purification, education, and so forth.

One of the functions of humor is to take its object down a peg. This is its value as well as its danger. Humor can be used to keep down people already low on the social totem pole, just as it can be used to corrode the prestige of the rich and powerful. As the late great Joan Rivers was fond of saying, laughter can be a way to cope with even the most serious or horrible things. The Onion’s finest moment was its first post 9/11 issue, poking its satirical finger directly into the fresh wound, and it was gloriously healing. In a more everyday setting, humor can “break the ice” by lowering the tenor of a situation, making it less formal or tense. But still, ethnic jokes, blond jokes, fat jokes, and others of that type too often function to perpetuate stereotypes, prejudices, and concrete material inequalities. As I suggested earlier, the difference between the appropriate and the inappropriate humor boils down to taste and context. But in all these cases, humor functions in essentially the same way: it tears things down.

People who teach about Islam tend to get annoyed by the general public obsession with Islamic veiling practices. Titles of news segments about “looking under the veil of Arabia,” “unveiling Islam,” or “removing the veil of secrecy from al-Qa’ida” hint at both assumptions about sexual repression in Muslim cultures and the titillation that comes from wondering what’s underneath. It’s all incredibly creepy when you think about it. Still, we know that the students are going to be coming in with veils on the brain, but yet they won’t necessarily know how to go about asking about it. At the beginning of one segment on gender relations, I started by telling the story of how I once tried on a burqa and proceeded to bump into everything. Everyone chuckles (whether out of true amusement or mere politeness doesn’t matter), but the most profane question is now on the table: How do they even see in those things? From there, the discussion can open up and bring in all sorts of different perspectives. I’ve signaled that the goal is not getting them to like or dislike the veil – and that it’s perfectly OK not to like it – but rather to understand a range of perspectives on the practice. No question will be considered offensive as long as it’s in the service of learning.

When teaching about Muhammad, I like to pull out a hadith (traditional narrative about the Prophet passed down by his followers) in which Muhammad is the butt of a practical joke by his wives. According to the narrative, Muhammad had a sweet tooth and loved honey-flavored drinks, which led him to spend a little bit more time with one of his wives (which one varies in the different versions) who exploited this fact by plying him with honey drinks. A’isha and several other wives decided to nip this in the bud by scheming to convince their husband that the honey beverage gave him bad breath and made him less sexy. He fell for it hook, line, and sinker, swearing off honey until their ruse was later revealed. While perhaps not a rip-roarer, it nevertheless allows us a chuckle at Muhammad’s expense. One of the reasons I like sharing this particular story is that I think it is originally intended to cause exactly such a chuckle. It’s an insider joke as much as an outsider joke. The hadith that highlight the Prophet’s home life paint a portrait of a human, relatable man suffering the everyday travails of married life. A real tension in Islamic thought stems from trying to revere and emulate Muhammad without making an idol out of him. The transmitters of this hadith take him down a notch without actually maligning him (Hadith involving A’isha do this a lot – her acerbic wit comes through so strongly that it’s easy to believe some real trace of her personality has made it through the hagiographies). Likewise, students of Islam ought to feel comfortable talking about Muhammad as a human being and probing what made him tick (to the degree you can based on what sources we have) if they seek to understand him and his followers.

In the classroom, the overall purpose is not the same as in a comedy club. At the end of the day, we do want students to have a healthy respect for the traditions and people they’re studying. At the same time, too much respect, or rather the wrong type of respect, can actually hamper learning. Humor is not the only way to cut through the untouchability of the sacred, but it can be effective, albeit potentially risky. For the downside is that for many within a tradition such treatment is the very definition of blasphemy, even if you’re not taking it to Rushdie-esque levels. I like to think I usually pull off the right balance, but I also freely admit that plenty of attempts fall flat or go too far in one direction or the other.

Religious figures get more than their fair share of lampooning on South Park, but we (usually, sometimes) love them for it

THE BOOK OF SOUTH PARK

Despite my prodigious comedic talents, my humor in the classroom or on Facebook feeds is incredibly tame compared what you can get away with on cable television these days. The work of Trey Parker and Matt Stone provides some great test cases for how humor can increase or fail to increase understanding of religions and religious sensibilities. South Park is a fascinating litmus test. I doubt there is anyone who has not actually been offended by something in the show sooner or later, but I also doubt if anyone who has seen the show has not been rewarded quite often with deep belly laughs. Religion is one of their favorite targets, and their perspective is certainly not that of believers, but nor is their depiction devoid of human empathy. The genius of Parker and Stone stems from their ability to invert their own inversions, flipping the mirror back at the audience, subverting the attitudes that made the comedy possible in the first place. It doesn’t always work – like all humor – but they’ve developed a very effective formula.

A great example can be seen in the infamous Muhammad episode (Episode 201, April 2010), which was censored by Comedy Central when it first aired and has not been aired at all since then (although leaked versions appear from time to time, I happened to watch it on its original night). Much like The Satanic Verses, the episode strangely explores the very type of controversy that came to engulf its fate in the real world. Stone and Parker received “credible” death threats from a fringe group based on the first part of their story in episode 200, leading the network to heavily edit 201, which in turn resulted in cries of censorship. The plot involves all of South Park’s past celebrity targets (Michael Jackson, Rob Reiner, Mel Gibson, Bono, Pope Benedict, robot Barbara Streisand, et al.) led by Tom Cruise suing the town in order to force them to arrange a meeting with the Prophet Muhammad. Cruise’s scheme is to subject the Prophet to a process that will extract the mysterious “goo” that renders Muhammad immune to ridicule and transfer it to the other celebrities (such a brilliant idea!). Throughout 200, Muhammad only appears hidden in a bear costume to disguise his identity. In 201, he always has a big black bar with “Censored” on it super-imposed on what was presumably the bear costume. There could almost be no better illustration of the concept of the Sacred that I discussed above, that what makes something sacred is not necessarily some inherent trait, but rather how people treat (or don’t treat) it. The South Park crew takes this idea a step further, at least in the uncensored version of the “final lesson” speech that was never aired.

KYLE: That’s because there is no goo, Mr. Cruise. You see, I learned something today. Throughout this whole ordeal, we’ve all wanted to show things that we weren’t allowed to show, but it wasn’t because of some magic goo. It was because of the magical power of threatening people with violence. That’s obviously the only true power. If there’s anything we’ve all learned, it’s that terrorizing people works.

JESUS: That’s right. Don’t you see, gingers, if you don’t want to be made fun of anymore, all you need are guns and bombs to get people to stop.

SANTA: That’s right, friends. All you need to do is instill fear and be willing to hurt people and you can get whatever you want. The only true power is violence.

The litigants in episode 200: I find it interesting that Mel Gibson is one of the few characters in South Park that, like Saddam Hussein, are animated with a photograph of their heads.

You don’t necessarily have to agree with the premise that respect for the Prophet needs to be predicated on violence (see my take on the Danish cartoons below). But it is true that the idea of the sacred frequently serves as a tool of power and social control. It’s important to note, though, that Muhammad is actually not the butt of the joke in this episode, although he’s certainly not an object of reverence either. Rather it is those who want to avoid ridicule to the point of threatening others. We’re looking at you, Mr. Cruise.

In an effort to combat the local belief that sex with a virgin cures AIDS, Elder Cunningham *slightly* embellishes the Book of Mormon by suggesting that God told Joseph Smith that all he had to do to cure himself of AIDS was to *ahem* “have intercourse” with a frog.

Their double-edged sword really shines in the musical The Book of Mormon, a long form treatment of religion. It is as crude, profane, and irreverent as South Park (without the bleeps!), but it humanizes religious belief in a way the audience may not have been suspecting. The plot follows a pair of young Mormon missionaries who are sent to Uganda, where they encounter AIDS, poverty, female circumcision, and violent warlords. It pokes fun at all the idiosyncrasies of the Mormon Church, such as its attitudes toward sexuality, concept of divinity, and conflicted history with converts of African descent. But unexpectedly, it is religious belief that ends up empowering the characters to face and overcome their obstacles. In what I think is the best song of the show, the main female character Nabulungi speaks of the inspiration she feels after learning of the early Mormons’ trek to the promised land of Salt Lake City. (Listen to it here.)

“Sal Tlay Ka Siti”

My mother once told me of a place

With waterfalls and unicorns flying

Where there was no suffering, no pain

Where there was laughter instead of dying

I always thought she’d made it up

To comfort me in times of pain

But now I know that place is real

Now I know its name

Sal Tlay Ka Siti

Not just a story Momma told

But a village in Oo-tah

Where the roofs are thatched with gold

If I could let myself believe

I know just where I’d be

Right on the next bus to Paradise

Sal Tlay Ka Siti

I can imagine what it must be like

This perfect, happy place

I’ll bet the goat meat there is plentiful

And they have vitamin injections by the case

The warlords there are friendly

They help you cross the street

And there’s a Red Cross on every corner

With all the flour you can eat

Sal Tlay Ka Siti

The most perfect place on Earth

The flies don’t bite your eyeballs

And human life has worth

It isn’t a place of fairytales

It’s as real as it can be

A land where evil doesn’t exist

Sal Tlay Ka Siti

And I’ll bet the people are open-minded

And don’t care who you’ve been

And all I hope is that when I find it

I’m able to fit in

Will I fit in?

Sal Tlay Ka Siti

A land of hope and joy

And if I want to get there

I just have to follow that white boy

You were right, Momma

You didn’t lie

The place is real

And I’m gonna fly

I’m on my way

Soon life won’t be so shitty

Now salvation has a name

Sal Tlay Ka Siti

Although the character seems naïve and unsophisticated, the song is nevertheless poignant and powerful. It hits the balance perfectly, in my opinion. It points squarely at the appeal and empowerment of apocalyptic narratives in which the crappy world we’re stuck in is replaced by a this-worldly utopia or other-worldly paradise. By imagining that things could be different and better, Nabulungi is no longer complacent in accepting the injustices around her, and she becomes a leader and agent of social change. Other numbers highlight the “Top 10” of religious themes, such as the origin of evil, the derivation of ethics from sacred stories, and the tension of differing scriptural interpretations. While it’s certainly not ground-breaking theology, the religious psychology of the characters is surprisingly multi-dimensional.

To my mind, what is most subversive about The Book of Mormon isn’t its skewering of religious faith. In fact, despite its irreverence, I wouldn’t consider it polemical against Mormonism or Christianity in general, at least not in the traditional sense. Rather, it attempts to get the audience to come out on the other side of the experience with a certain amount of empathy for people and ideas they were simply expecting to be able to mock. This is why I think Bill Maher fails in his critiques of religion. His one-note shtick is basically to say, “Look how stupid those religious people are.” Parker and Stone might also say that, but they don’t stop there, opting instead to humanize and complicate the objects of their satire. Sure, they remain abject and ridiculous, but the audience is prevented from simply adopting an attitude of smug superiority. If they had a credo, I think it might be “Ridiculousness and stupidity are part of the universal human condition.” Interestingly, the Latter Day Saints leadership responded to the production with a good deal of equanimity, even to the point of advertising in the playbill that “You’ve seen the play, now read the book.”

IT’S JUST A CARTOON, MAN

While Mormons have certainly experienced oppression and violence in their history, in 21st-century America there is no fear that riled-up audiences will leave a production of The Book of Mormon and start beating up random Mormons on the street or refusing to give them jobs because of their faith. While the show certainly laughs at Mormons more than with them, Mormons exist in a safe-enough social space that they can feel free to choose to laugh with those laughing at them, or not. Even though he didn’t win, the fact that Mitt Romney secured his party’s nomination for the presidency was historically significant, just as Kennedy’s election signaled to American Catholics that they were no longer a maligned minority (or at least, they no longer needed to care if they’re maligned in some quarters).

But I’d like to take a cue from Trey and Matt and invert the inversion. I had a very different reaction to the Muhammad cartoon controversy in 2005 than most everyone else. Doubtless that was in part because my interests create a certain sympathy for Muslim perspectives. But actually, the first thing that occurred to me was how similar some of the cartoons were to some of the anti-semitic cartoons from pre-WWII Europe I was familiar with. While the question of free speech and the place of blasphemy laws in a free, secular society is a valid and important one, what most struck me was how far right-wing groups throughout Europe gleefully piled on the “let’s ratchet up the offense against Muslims” bandwagon. To be honest, most of the original cartoons were pretty innocuous. The most potentially offensive ones to my eyes were the one with a bomb in Muhammad’s turban and the one in which the Prophet appears with a black censor-stripe across his eyes and wielding a sword barring access to two veiled women with an open stripe that leaves only their eyes visible. While the former struck me as simply mean-spirited, the latter at least had a clever visual hook. Unfortunately, when some Danish imams compiled their dossier of the cartoons to send to their colleagues in the Middle East, they included some very-amateurish images that were over the top-offensive, such as a photo-manipulation that shows a praying Muslim man being sexually mounted by a dog (considered an unclean animal by many Muslims, making it even worse) with the caption: “This is really why Muslims pray prostrate.”

It’s significant that the response of U.S. Muslims was far more muted than their counterparts in Europe. The crazy Islamophobic rants one sees on FOX and weird FBI entrapment schemes notwithstanding, Muslims in the U.S. are not in the same kind of embattled position as in Europe. This is due to numerous factors, including the smaller size of the American Muslim community with respect to the majority, their largely middle-class and educated status, and the fact that American legal institutions protecting freedom of worship are fairly robust (and indeed are more interested in protecting religion from the state than the state from religion, for better or worse. I’d say largely for better). A better, if still inadequate, American analogy for the status of European Muslims would be the case of American Latinos. All the right-wing rhetoric about the dangers of immigrants to “our” language, jobs, culture, and morality are directed at Muslim immigrants instead. Europeans have the additional hurdle that they are less accustomed to imagining themselves as multicultural societies. Laws curtailing Muslim religious expression and practice, such as banning Islamic dress in schools or limiting the construction of mosques are becoming commonplace, and were in fact reaching a fever pitch around the time the cartoons were published. The cartoons thus struck many European Muslims as yet another attack denigrating and marginalizing their place in European society.

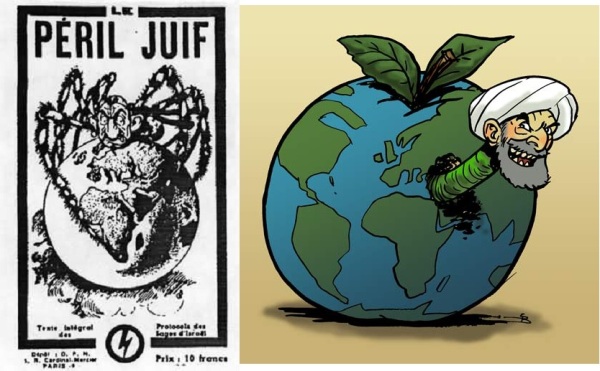

Left is a 1934 cover of a French translation of the Anti-Semitic “Protocols of the Elders of Zion”; Right is a depiction of the Muslim threat from right-wing French cartoonist Steph Bergol (not one of the Danish cartoons)

The cartoons, or rather the context and intent behind them, made me think uncomfortably of pre-World War II political cartoons depicting Jews, who were often mocked for trying and failing to assimilate into “mainstream” European society. Even the physicality of the caricatures, such as an exaggerated hook nose, bushy unkempt eyebrows, and lascivious leer were reminiscent of anti-Jewish imagery. In some of the popular political cartoons that appeared in the wake of the controversy that sought to ramp up the level of offensiveness to make a point, much of the imagery seems deliberately cribbed from a century ago. Muhammad menacing a globe, leering at unsuspecting European women, and pulling the strings behind government policies that dilute the power of traditional (white) dominance. In short, unlike the satire of The Book of Mormon, the goal of many such cartoons was to de-humanize Muhammad and Muslims as a clear and present threat.

There’s a limit to such a comparison, of course, and I don’t think we’re on the verge of another genocide, but I believe the storm around the Muhammad cartoons were just as much about racist animus as about critique of religious fanaticism. Censorship or asking for censorship isn’t the solution in such cases. Nor do I think the success of multiculturalism depends on a punitive system of political correctness (in fact, I think it ultimately undermines it). The best response is perhaps to turn the comedic tables, as one of the 12 original Danish cartoonists did by depicting Kåre Bluitgen, the children’s author who complained of his difficulty finding willing illustrators for his children’s book about Muhammad and who thus started the ball rolling, dressed in a turban with an orange with the words “PR-Stunt” written on it – visually similar to the more famous image of Muhammad with a bomb in his turban.